Each of the seven short pieces in Ignoble Dances draw musical influence from a variety of sources. Written in 2020, its music reflects upon that disconsolate year. The title of the first movement, Antemasque, refers to a “buffoonish dance” that precedes a masque, a courtly entertainment of the 16th century. Of course, “anti-mask” gained another meaning in 2020. Denial, Duplicity, Dog Whistles: all played a role during the turbulent year 2020, and all make appearances in the seven pieces that make up Ignoble Dances. The set concludes with a pavan: a slow, stately Renaissance dance. In 1648, composer Thomas Tomkins wrote a lament in memory of King Charles I, entitled “Sad Pavan for These Distracted Tymes.” In Al-Zand’s pavan, which draws on the Tomkins, it is the music that is distracted and the times that are sad.

1. Antemasque

2. Dance of Duplicity

3. Dance of Denial

– the first mention of the Tarantella, from the 15th century

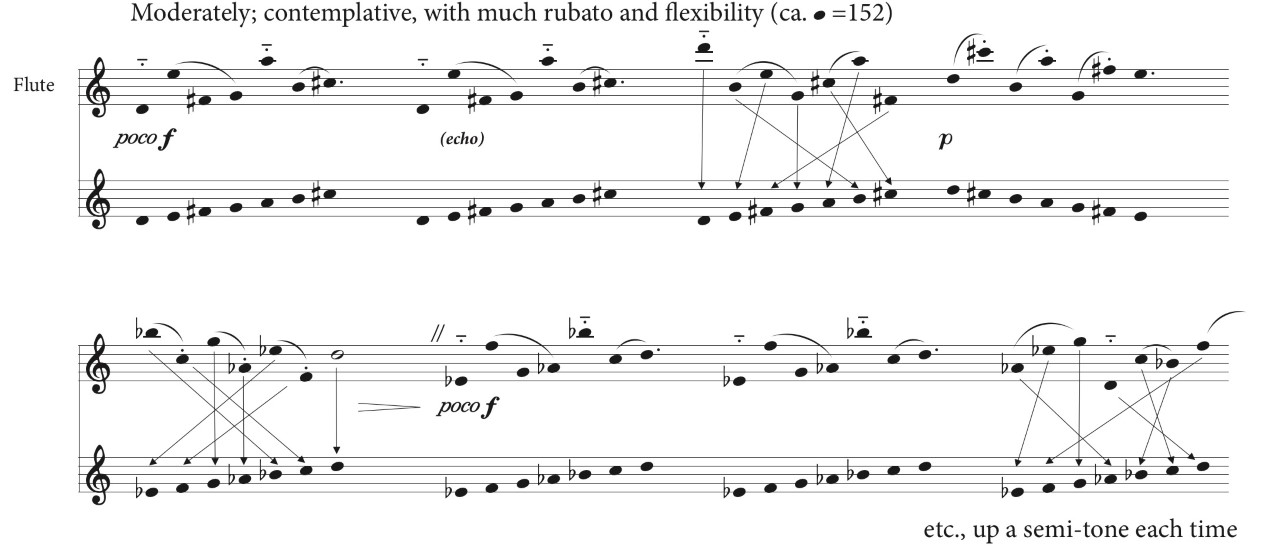

4. Distanced Dance

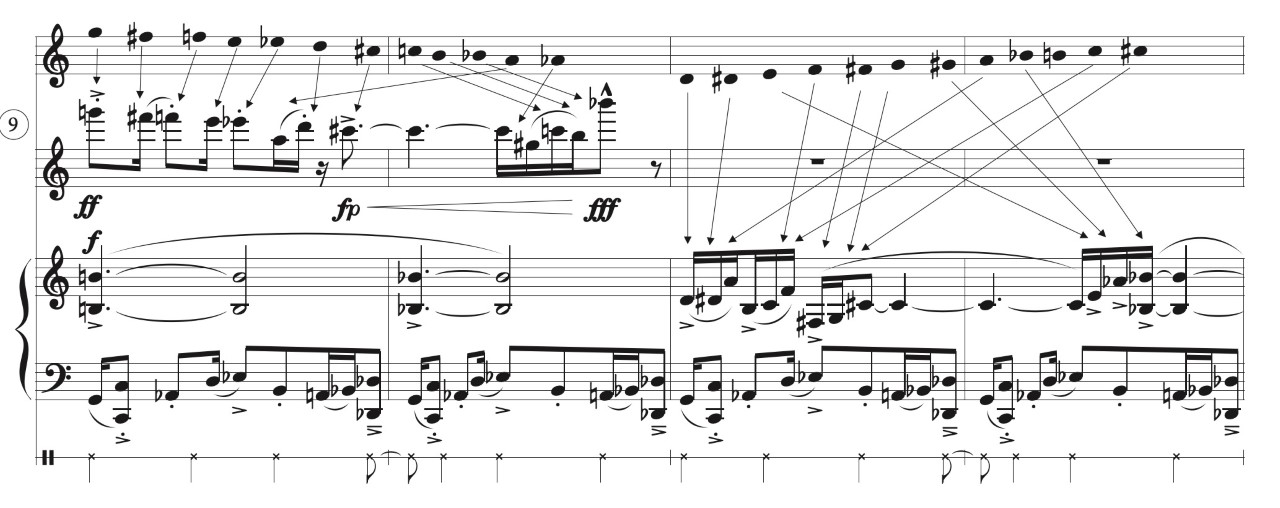

5. J.B. Dances a Jig in the Gloom

6. Dog Whistle Dance

7. Distracted Pavan for These Sad Times