Sound Reasoning

Table of Contents

Part II: Hearing Harmony

18.1 Hearing Harmony: What is Harmony?

18.2 Harmony in Western Music

18.3 Expressing Harmony

18.4 Listening Gallery: Expressing Harmony

18.5 Harmonic Rhythm

18.6 Listening Gallery: Harmonic Rhythm

18.7 Cadences

18.8 Listening Gallery: Cadences

18.9 The Tonic

18.10 Circular and Linear Progressions

18.11 Listening Gallery: Circular and Linear Progressions

18.12 The Major-minor Contrast

18.13 Modes and Scales

18.14 Hearing the Mode

18.15 Listening Gallery: Hearing the Mode

18.16 Tonic, Mode and Key

18.17 Listening Gallery: Tonic, Mode and Key

18.18 Music Within a Key

18.19 Listening Gallery: Music Within a Key

18.20 Postponed Closure

18.21 Listening Gallery: Postponing Closure

18.22 Chromaticism

18.23 Listening Gallery: Chromaticism

18.24 Dissonance

18.25 Leaving the Key

18.26 Harmonic Distance

18.27 Modulation

18.28 Harmonic Goals

18.29 The Return to the Tonic

18.30 Final Closure

18.31 Listening Gallery: Final Closure

18.32 Reharmonizing a Melody

18.33 Listening Gallery: Reharmonizing a Melody

18.34 Conclusion

18.25 Leaving the Key

Whereas diatonic progressions remain within a key, modulation involves moving between keys. Because it involves uprooting the music from a tonal center and moving to others, modulation is the most action-oriented part of harmony.

The structural import and expressive impact of a modulation is derived from the inter-relationship of three factors:

The “harmonic distance” travelled – the time spent in travel – the time spent in arrival

In order to understand this more fully, we need to explore several concepts about Common Practice tonality.

The Structural Equivalence of Keys

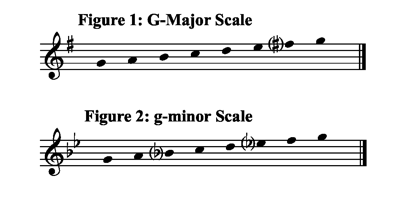

As noted earlier, the term key of the music indicates the tonic and mode. Thus, music in the key of G-Major makes use of the Major scale built on the tonic G; the key of g-minor shares the same tonic—g—but is in the minor mode.

Any pitch of the chromatic scale may serve as the tonic: Thus, there are twelve possible keys for each mode.

In modern tempered tuning, all keys of the same mode are functionally equivalent: They are like Club Scout chapters, sharing the same charter, hierarchy of officers and rituals. For example, singers sometimes find a song may lie in an uncomfortable range; so they transpose it to a higher or lower key. The music remains the same: It just slides up or down.

Here are two performances of Franz Schubert’s song Gesang des Harfners II: The music is identical except for the transposition.

Because of this equivalence, it is possible to move from key to key without any modification in musical syntax. Put another way, the rules of harmony don’t change when you change keys. This harmonic consistency makes the modulation intelligible: No written explanations or verbal remarks are required. What holds true in one key holds true in any other.

Musical commentators often speak of the “coloring” of different keys. This has largely to do with instrumentation: For instance, the keys of G, D, A and E sound “brighter” on string instruments because they allow for the use of open strings. Similarly, marches are typically in B-flat Major because of how brass instruments are tuned. Interpreters sometimes ascribe meaning or significance to particular keys: C-Major is Mozart’s “Coronation” key, “c-minor” is Beethoven’s key for funerals, etc. Applied too literally or categorically, however, these associations risk obscuring the underlying consistency upon which tonality depends: All keys of the same mode share the identical structure and their progressions are organized the same way.